Last month, when site work and travel were still a reality I worked on a fascinating conservation project on domestic wall paintings in a house in a village outside Oxford.

Cromwell House dates from around 1600 and is grade II listed. It is a stone building, with a thatched roof. It was recently purchased by the current owners, having previously been in the same hands for more than 50 years – and with the interior seemingly more or less untouched since the 1960s.

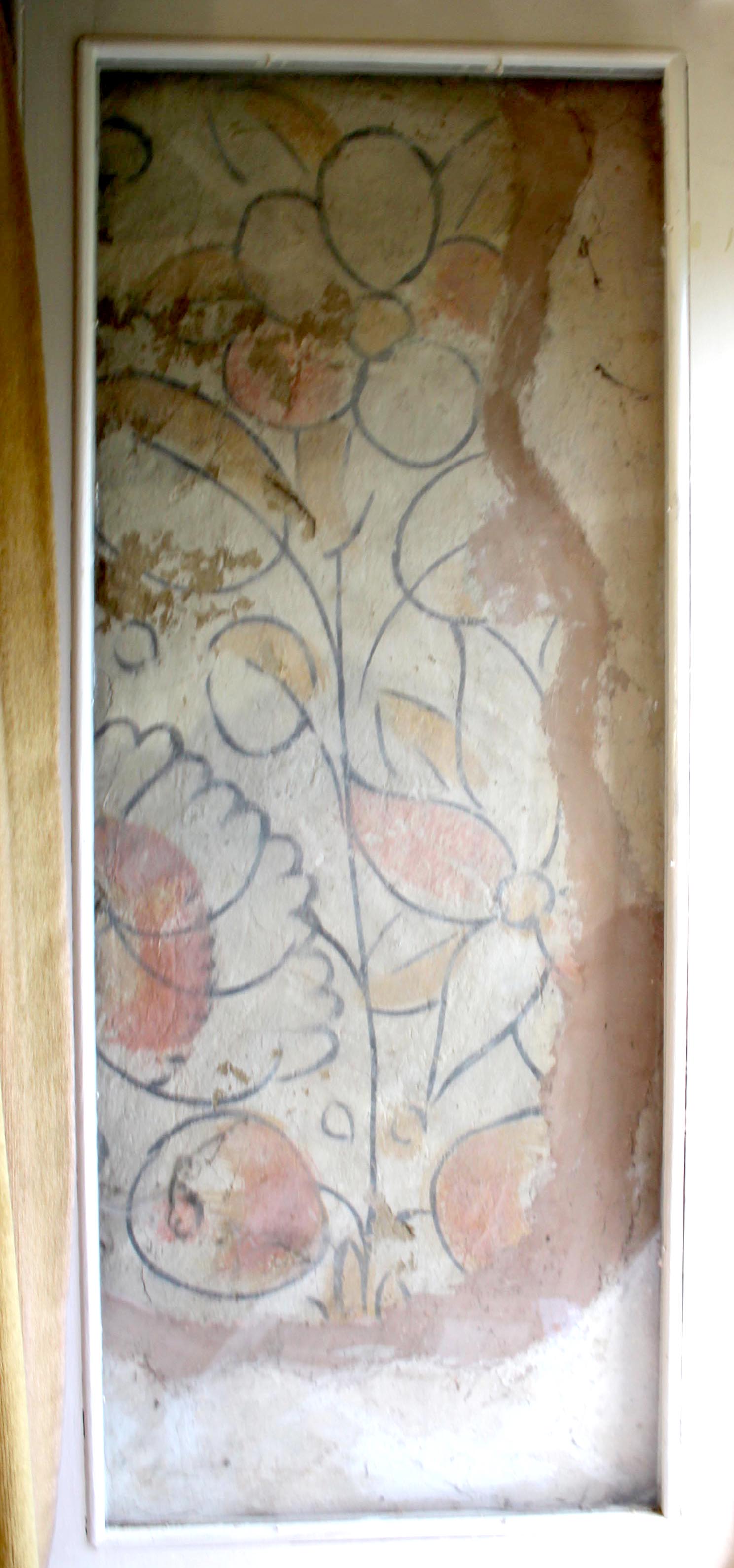

At the time of the purchase, the new owners were aware of two areas of wall painting – in window splays and associated with the windows on the north walls on two of the three downstairs rooms. These paintings had been previously revealed and were framed and displayed behind glass.

1 – 4 The already revealed areas of painting

But on starting work on the interior of the house, removing 1960s partitioning and cement plastering on the lower parts of the walls it became clear that there was, in fact, a considerable quantity of surviving wall painting on the upper parts of walls and in areas which had not been significantly reworked. This decoration was beneath layers of covering modern and historic paint and plaster.

The two ground floor rooms of the house (the walls of the third have been altered substantially and historic plasters seem to have been lost in the process) appear to have been covered throughout with a scrolling foliate/floral pattern – with the painting covering window reveals, lintels, and the main walls as well as the passage which connects the two rooms.

5 & 6 Painted beams and a large area of painting revealed over the fireplace

In addition to the foliate design, one of the previously revealed areas of painting had a figurative painting – a figure playing a bagpipe. This could be dated to the early 1600s by the clothing depicted. The newly discovered areas of painting revealed another figure in the connecting corridor between the two rooms – a male figure with a moustache and what appears to be a feather from a hat. It is not currently clear how the figurative painting fitted into the foliate pattern, this would only be understood with further uncovering of the surrounding areas. It appeared as if an exposed area next to that of the corridor male figure could be another figure- with the scrollwork revealed reading as possibly the edges of epaulettes similar to those of the pipe player, as well as the lower part of a ruff.

7 & 8 The newly revealed male figure, left, part way through the conservation and stabilisation treatment, and right, the area of painting next to it, which may also be a part of a figure

The palette used for the painting is typical of the period – with pigments likely to include chalk white, charcoal black, red and yellow ochre, indigo/woad and green earth (pigment analysis which precisely identifies the pigments will be undertaken as part of a later in-depth conservation project).

Domestic wall paintings such as these were very common in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, with bold and brightly coloured designs – see also: Sibleys Wall Paintings. Paintings would be, as at Cromwell House, in the principle rooms. The skill level of the painting is not necessarily very sophisticated, as they were often executed by building craftsmen rather than specialised painters.[1] The scale and complexity of the scheme would be relative to the wealth of the owner.

My work on the paintings involved a survey at Cromwell House at the beginning of the year to make a thorough on-site assessment of the extent of the surviving wall painting, as well as the covering layer structures, and to record the areas room by room.

Following recording, I also drew up a conservation treatment proposal for the emergency stabilisation of the surviving decorated plaster, to be carried out before any further building work was undertaken in the house. The proposal also identified areas of painting for future in-depth conservation work – notably those areas of painting which were already uncovered and displayed under glass, as well a large newly exposed area of painting.

The emergency conservation work was undertaken in a second phase of work at Cromwell House –and included stabilisation of detachments within exposed areas of the original painted plaster and the support of vulnerable edges of the original decorated plaster – it aimed to stabilise these at-risk areas before a phase of interior building work is undertaken.

9 & 10 Grouting and edge repairs to unsupported edges of painting

The emergency treatment also included the fixing of flaking paint, powdering paint layers, dry cleaning to remove surface dirt and some emergency work on the very vulnerable figure of the pipe player.

11 & 12 Emergency stabilisation of the pipe player, and right, the large area of newly exposed painting over the fireplace, after the emergency consolidation – it will be fully treated in an in-depth conservation intervention at a later date

The majority of the incidentally exposed and fragmentary painting will now be protected and recovered, with a specifically constructed system of a subframe (which does not touch or attach into the plaster surface) with panelling of a compatible breathable material proposed, subject to listed buildings consent.[2]

The in-depth conservation work on the areas of exposed painting and the one large area of newly exposed painting is something to look forward to at a later date – likely next year. As a part of the full conservation treatment the glass which currently covers the previously uncovered paintings will be removed, as, while it does offer physical protection during the building work, and has been in place for some time, keeping wall paintings behind glass/impermeable materials risks creating a microclimate, such coverings prevent the natural exchange of air and moisture through the materials, effecting their breathability and can lead to traps of moisture and damp.

13 & 14 Cleaning tests to inform later conservation work on the large area of exposed painting over the fireplace, and the pipe player, after the emergency work

The conservation work will include pigment analysis, surface cleaning, further stabilisation as necessary, the reduction of the rather clumsy current pink plaster repairs, sympathetic lime mortar and fine repairs to fill losses and cracks and reintegration – to tone in the repairs and losses to allow the paintings to read coherently without the current interruptions of losses, damages and old repairs.

With many thanks to my colleague Claudia Fiocchetti, who worked with me on the stabilisation phase of the project.

[1] Dr Kathryn Davies, 2020; Cromwell House: An Assessment Of The Significance Of The Wall Paintings

[2] This protection could be easily unscrewed and disassembled at a later date