The shrine of Ikhwat Yusuf (AD 1125-50) is a rare Fatimid mausoleum located in Cairo’s City of the Dead. It is one of Egypt’s very few surviving Fatimid buildings to contain a decorated and carved stucco mihrab – and one of only two with a surviving triple mihrab.

This spring I worked as the lead conservator at Ikhwat Yusuf on the mihrab and the multiple plaster layers on the lower part of the walls of the mausoleum, which held historic pilgrim texts. The project was for the American Research Centre in Egypt, and part of the wider ARCE project that commenced in 2022, which addressed the building structure and its long-term protection, preservation and presentation as a whole.

The mausoleum was in extremely vulnerable condition before the start of the project. It had deteriorated over time, with the collapse of a wall and loss of ceilings. This had enabled uncontrolled human access – allowing graffiti of the walls, among other impacts. Rising external ground levels had further eased access to the interior, which also had a steady build up of rubble. Fire damage inside the building meanwhile had led to heavy soot deposits across the walls and ceilings.

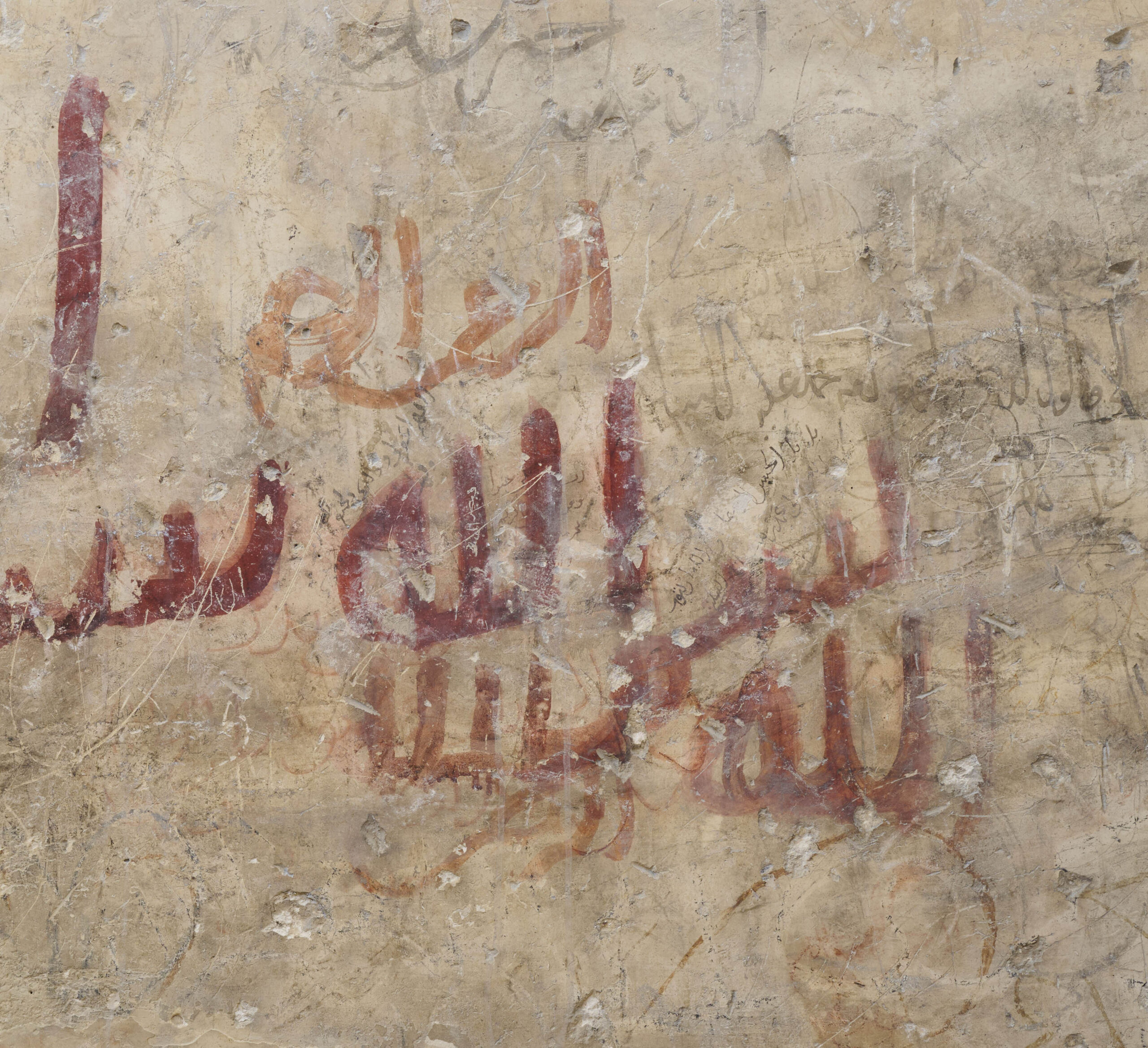

Stucco and carved elements were lost from the mihrab, which had a heavy layer of dirt and soot, and the niches were graffitied. The wall plasters meanwhile, had aged and deteriorated over time in different ways, leading to detachments and losses at the lower parts, while the surfaces were covered with soot and modern graffiti which covered and obscured the historic pilgrim texts.

The conservation work, which followed 3D laser scan documentation that provided a pre-conservation record of condition, aimed to stabilise the historic plasters and the mihrab, reducing the damaging and disfiguring deposits with a cleaning level that enabled the historic surfaces to read, without losing patina or risking damage to the texts. The approach was, in keeping with current conservation ethics, minimal intervention. It did not attempt to recreate missing elements but to stabilize and allow surfaces to be understood in the context of the history of the building.

I had tested a series of traditional cleaning methods and solutions on the dirt deposits on the mihrab during initial assessment in 2022, but, due to the soft and pitted nature of the stucco, and the heavily ingrained dirt, it was not possible to reduce them in this way without risking softening the stucco and mixing solubilized dirt into it.

Conservation laser cleaning was therefore selected as the ideal cleaning method for this type of very pitted, uneven and also extremely fragile surface, it involves no direct contact and can lift dirt without the risk of damaging the delicate material through abrasion or pressure. The laser used was a Q-switched laser system, operating in the 1064nm wavelength. It was a 50 watt backpack laser from Clean Laser, Herzogenrath, Aachen, Germany.

The laser worked extremely successfully on the carved stucco of the mihrab, and on the graffitied niches, it could also be used without affecting the historic red texts in the niches but at the same time removed the modern charcoal graffiti.

Above details of the laser cleaning process on the niches and the carved plaster of the mihrab (top image M Perry for ARCE, all other images B Madden for ARCE)

A slightly different method was used for the wall plasters – many of the historic texts were black ink, meaning the laser, which works on the principle of dark materials absorbing light, could not be safely used in these areas. Traditional solution cleaning methods worked well on this plaster, but the modern charcoal graffiti could not be removed without a much heavier cleaning level using solution-based methods. Selective cleaning in this way would actually have emphasized the graffiti’s presence, resulting in much whiter haloes around the area it had been, and an uneven appearance to the walls, while, if a heavier traditional method was extended across the walls, it would have risked losing the historic surfaces and texts.

Following testing it was established, however, that, after light traditional cleaning, the laser could be used almost as a brush, holding the handpiece at a further distance than usual, to pass the beam very gently over the area with the modern charcoal graffiti – with the beam just touching its surface. This way, with a series of extremely gentle brushes, it was possible to reduce the modern graffiti without removing historic material or cleaning the plaster beneath more than could be safely achieved in the areas with the texts.

An area of historically inscribed plaster, above (image M Perry for ARCE) before cleaning, below (image M Kacicnik for ARCE) after tradition cleaning and selective use of the laser for the charcoal graffiti

As well as cleaning, stabilisation was undertaken using repairs and grouting as required on both the mihrab and the wall plasters. Repairs were not used to fully fill missing areas unless this was required for structural reasons, instead, they held and supported the layers and vulnerable edges – in an archaeological conservation approach which allowed the stratigraphy of construction and the historic interventions to be read.

Cover image M Kacicnik for ARCE – the mihrab after conservation

An article about the wider project at Ikhwat Yusuf can be found here: https://arce.org/project/the-shrine-of-ikhwat-yusuf-restoration-and-training-in-medieval-cairo/ on ARCE’s website.

And here is a piece about the Clean Laser laser and its application in conservation cleaning: https://www.cleanlaser.de/en/applications/application-fields/restoration-and-conservation/